“True character is revealed in the choices a human being makes under pressure. The greater the pressure… the truer the choice to the character’s essential nature.” –Robert McKee, creative writing instructor

On Tuesday, October 8th Quantic Dream’s Beyond: Two Souls will hit the PS3. This highly-anticipated follow-up to 2010’s Heavy Rain—which won multiple “Game of the Year” awards for its groundbreaking approach to interactive storytelling—stars Hollywood actress Ellen Page, and is likely to become the fastest-selling interactive narrative ever created.

“Interactive storytelling” has always been a bit of a quandary. Story, at its heart, is about revealing character through choices. Stories are therefore often structured to put characters through hoops and force them to change in some way. Many writers will even tell you that structure and character are two sides of the same coin, inverse equations if you will. Stories, according to popular theory, are built on structure and are inseparable from their characters.

Consider the recently-concluded Breaking Bad, which is almost entirely about the choices of Walter White. In the pilot, he’s a mild-mannered chemistry teacher whose cancer diagnosis leads him to make a small criminal decision. Over the next five seasons, his bad choices escalate, ultimately resulting in the dramatic events of the finale. This is a great example of story, character, and structure all coming together; unsurprisingly, the show won an Emmy for Best Drama just a week before it ended.

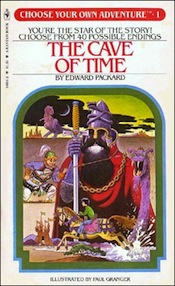

Only there’s more to this story—no pun intended. In the 1980s, I loved those popular “Choose Your Own Adventure” books. You’d open the book to page one and read a story told in the second person (YOU are the main character), about, say, your visit to the Statue of Liberty. Within a couple pages, you’d be given a choice: if you follow your sister, turn to page 4; if you follow the stranger, turn to page 7. Whatever you choose, the story branches and branches until you reach one of many possible endings. Never content with just one, I’d always go back and see where different choices might have led me.

Only there’s more to this story—no pun intended. In the 1980s, I loved those popular “Choose Your Own Adventure” books. You’d open the book to page one and read a story told in the second person (YOU are the main character), about, say, your visit to the Statue of Liberty. Within a couple pages, you’d be given a choice: if you follow your sister, turn to page 4; if you follow the stranger, turn to page 7. Whatever you choose, the story branches and branches until you reach one of many possible endings. Never content with just one, I’d always go back and see where different choices might have led me.

This experience was an early example of interactive storytelling—a phrase which refers to any story (though usually one in a videogame) where the player makes decisions that affect the story’s outcome. This might mean branching paths, like in a “Choose Your Own Adventure” book, or a central storyline with side quests that split off and return to the “story spine,” or a linear story with flexible dialogue options, or even just an conventional tale with multiple endings. Today’s games often feature some combination of all of these, and a variety of experimental approaches as well.

But there’s a basic challenge that all interactive storytellers face: structure and freedom are antithetical. Simply put: if a player has total freedom, then there’s no room for a writer to tell a story (think Second Life). On the other hand, you can tell a pretty awesome story if you limit a player’s choices—but as it turns out, players don’t like being given “false freedom.” (That’s what often happens in Japanese RPGs, including Final Fantasy titles; these games’ stories, although beautifully animated, are usually completely linear.

There is a middle ground, of course. The Dragon Age games allow player choices to affect character morality, and those moral decisions shade how the world responds to them. The Elder Scrolls games feature a short central storyline, but the bulk of the game is open world. In Telltale’s adventure game The Walking Dead, each chapter includes a “Sophie’s Choice” moment in which players must make a quick, life-or-death decision that affects other characters and the game’s final reckoning. Each of these games has its own trade-off between traditional storytelling and interactivity.

However, nobody has been quite as innovative in interactive storytelling as Quantic Dream, the company behind Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls. Heavy Rain was essentially an interactive movie—a noir thriller in which the player controls the moment-to-moment actions of four characters close to the case of the game’s fictional “Origami Killer.” It wasn’t the first time someone had attempted to make an interactive film—that phenomenon dates back to the early days of CD-ROM—but it was the first time anyone had done it like this. Featuring gorgeous cinematography, fully-3D characters, a gripping storyline, and a cinematic score, Heavy Rain was a huge critical success and essentially redefined interactive storytelling overnight.

In Heavy Rain, your real-time action and dialogue choices determine what, in story parlance, would be called “beats”—things such as whether a character throws a punch or lights a cigarette, what dialogue (if any) they choose say to another character, and even the discursive thoughts rumbling around their heads as they shower. For the first half of the game, this sets up a dynamic where the player feels in control, but the story and characters are unfolding linearly—which needs to happen if a player is going to get emotionally invested. But as the story progresses, your choices begin to actually matter. The climax of the game can play out one of eight ways, and each main character has between four and seven endings—meaning there are literally hundreds of ways a player can experience the third act.

Does the game sacrifice some degree of emotional impact in the name of interactivity? For sure. There’s no denying that you’ll feel varying degrees of satisfaction depending on whether the brooding main character finds peace, love, or death at the end. But the game makes these trade-offs intentionally, using different kinds of player freedom at different points to keep players in control yet emotionally hooked. The result is a tight, nuanced, and believable story that plays very much like the interactive movie it’s intended to be.

If early reports are any indication, Beyond: Two Souls is even more sophisticated than its predecessor. David Cage, the mastermind at Quantic Dream, essentially had carte blanche after the success of Heavy Rain, and wrote Beyond’s entire 2000-page script by himself. The game allows players to explore fully 3D environments, switch between a human character and a disembodied entity, and control a story much larger in scope than the case of the Origami Killer. Early buzz has been positive, though we’ll have to wait and see if the game lives up to the hype.

But regardless of hype, these games—along with titles like The Walking Dead—are ushering in a new era of interactive storytelling. And that’s what’s so exciting about the genre: there’s still so much room for growth. Every year sees the release of a title that breaks new ground, and with the new consoles almost here, it’s anyone’s guess what will happen next.

So if you’re excited to play Beyond: Two Souls, turn to page 14. If you’d rather replay Heavy Rain, turn to page 9. If you want to read the reviews first, turn to page 84. And if you’re that rare person who feels inspired to create your own interactive story… turn to Page 1 and get started.

Brad Kane is a writer focusing on storytelling in movies, TV, videogames, and more. If you enjoyed this article, take a second to check out his blog and/or like his page on Facebook. He also has a new Twitter account that he is trying to remember to use.